Workplace Violence: it’s more common than you think (2 in 2 part series)

This is a 2-part series. If you missed the first part, read it here

People need to feel safe at work. Period. In environments where people are physically aggressive or intimidating, people are hindered from performing their best. Research has shown that even being paired with an intimidating and competitive person negatively impacts performance levels.

This is because threatening situations activate the survival/reptilian brain, which cuts off access to their higher-thinking abilities including innovation and creativity. Needless to say, this also harms the organizations where they work.

Many of us think that physical safety at work is a given these days, but workplace violence and aggression are surprisingly prevalent, both among peers and between supervisors and employees. According to the National Safety Council, every year two million Americans are the victims of workplace violence. About 16 percent of workplace deaths are the result of an attack in the workplace. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health analyzes the source of all kinds of workplace injuries and has identified four types of workplace violence:

- Criminal intent (such as a burglary)

- Customer and/or client

- Worker on worker

- Personal relationships, where the greatest number of victims are women

Some industries are more prone to workplace violence than others. It’s the third leading cause of death for healthcare workers, and taxi drivers are twenty times more likely to be murdered on the job than any other worker. Men are the most likely victims at 83 percent of workplace homicides. I was shocked to learn that over one-quarter (26.1 percent) of workplace homicide victims work in sales or retail, higher than those in protective services (19.1 percent) including police officers and security guards.

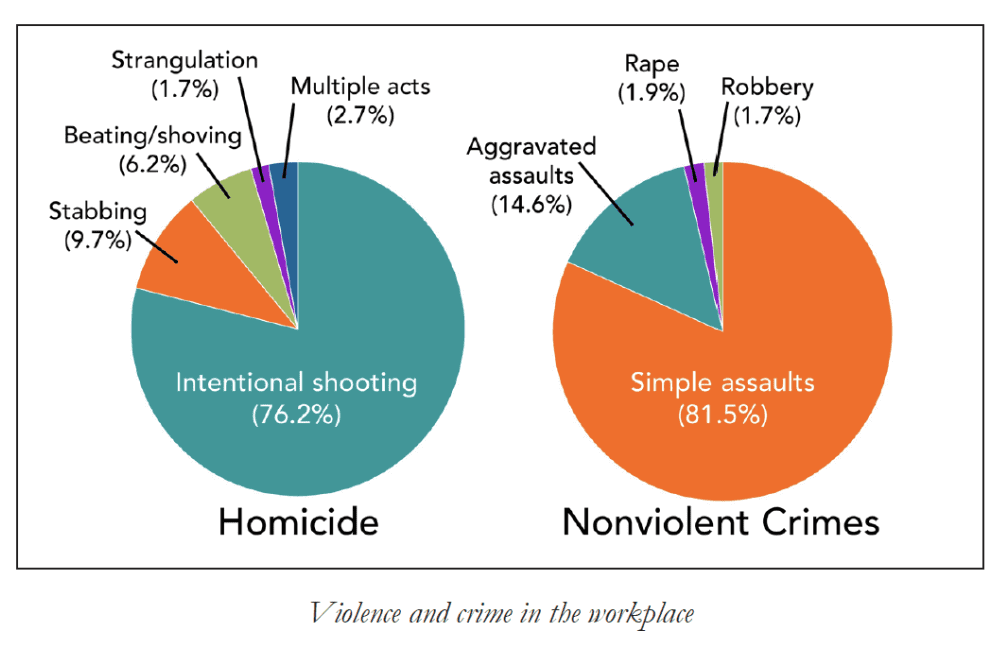

Of course, we have all seen the damage done by active shooters in the workplace, often injuring or killing several people within minutes. In fact, intentional shooting is the most common mode of workplace homicide (76.2 percent), followed by stabbing (9.7 percent), and beating/shoving (6.2 percent). Nonfatal violent crimes also plague workplaces with the most common crimes being simple assaults (81.5 percent) and aggravated assaults (14.6 percent) followed by rape (1.9 percent) and robbery (1.7 percent).

Of course, we have all seen the damage done by active shooters in the workplace, often injuring or killing several people within minutes. In fact, intentional shooting is the most common mode of workplace homicide (76.2 percent), followed by stabbing (9.7 percent), and beating/shoving (6.2 percent). Nonfatal violent crimes also plague workplaces with the most common crimes being simple assaults (81.5 percent) and aggravated assaults (14.6 percent) followed by rape (1.9 percent) and robbery (1.7 percent).

From this data, it’s clear that for many, physical safety on the job is a valid and present concern. But separate from potential harm, our sense of physical safety also depends on keeping our job, as our paycheck is the way we buy food, water, and shelter—the essentials of survival. So threatening to fire someone can have nearly the same emotional impact as threatening to hit them, launching a person into the fight-flight-freeze response. Several studies have shown that the amygdala is active during standard work performance reviews, signaling just how threatening the experience can seem.

Many aspects of our biology are designed to help us connect with others, but lots of things can get in the way. We only truly connect when we are safe enough to do so—in other words, when we don’t feel threatened, physically or psychologically. That seems to be a mandatory condition to bring our whole selves to work and to perform at our best. The safer we feel, the better we perform. Biologically, we can access more of our higher thinking functions and we don’t waste energy on constantly scanning our environment and protecting ourselves.

Creating Inclusion

A sense of belonging matters. We don’t need to be popular or liked by everyone but we do need to have a sense of belonging somewhere, with someone. This has lots of implications for workplaces today. Employee engagement is not just a measure of work pride and productivity, it’s also a valuable indicator of inclusion and exclusion. This is why it’s so important that measures of engagement include questions like, “Someone at work cares about me as a person,” or “I have a friend at work.”

This is also why orientation or onboarding efforts are more effective when companies go beyond the basics of new employment and help people integrate socially into their new community. Did you know that one-third of new hires quit their job within six months of starting it? According to a 2014 study by BambooHR, 17 percent said that a friendly smile or a helpful coworker would have made all the difference. Nearly 10 percent wished for more attention from their manager and coworkers.

A study by the Aberdeen Group found that high-performing organizations are two-and-a-half times more likely than lower-performing ones to assign a mentor or buddy during onboarding. This small and affordable effort helps new hires feel connected, plus their experience is seen by someone who can advise and guide them should they hit challenges.

These findings are not a surprise to me. As someone who has run onboarding for both small and large organizations, including a multinational company of 10,000 employees, I can tell you that the ability to “find your tribe,” even if it’s just a tribe of one, can make all the difference. Again, companies with the best new-hire retention purposefully help their newest members navigate the structural and social elements of a new environment.

And it doesn’t just end at onboarding. Inclusion, or lack of it, is woven into every aspect of an organization from how managers conduct one-on-one meetings to how brainstorming and team project meetings are conducted. It’s reflected in who has seats at the leadership table and how people address acts of exclusion or marginalization.

Fostering inclusion in your workplace doesn’t necessarily protect against workplace violence, but it does go a long way toward creating a safe space for people to speak up when they need to. On a strong team, people trust each other, listen to each other, and look out for each other.

Here are some additional resources:

This was an excerpt from my book Wired to Connect: The Brain Science of Teams and a New Model for Creating Collaboration and Inclusion.

Related Blogs

JOIN OUR COMMUNITY

Be the first to know of Dr. Britt Andreatta's latest news and research.