Building High-Performing Teams

Building High-Performing Teams

"There is no I, in team"

Vernon Law, baseball player, 1960

Most of us have heard that phrase at some point in our lives. I certainly have—in fact, that quote has sat on my desk in every place I have ever worked. But you know what? It’s wrong. When I started researching the neuroscience of teams, I wasn’t aware that I would end up questioning such an iconic belief. But the brain science of what brings out the best in groups points us in a new and surprising direction.

The best teams, the highest-performing ones, create a cohesive unit through honoring each member’s unique contributions and making them feel included and valued for who they are, as individuals. It turns out there is an I in team. In fact there are lots of I’s. Every team is made up of individuals who bring their own perspectives, skill sets, and experiences. Not only do team environments need to leverage the gifts of those individuals, the group needs to make its members feel safe enough to bring their best work forward. When this is done right, members feel they belong and the group is set up to achieve a rarefied state of peak performance, one that is neurologically different from the rest.

While we are biologically wired to connect with others, critical conditions must be met to drive peak performance at work. Recent discoveries in neuroscience illuminate what differentiates the highest-performing teams from the rest. And because brain biology is universal, these discoveries apply to all, cutting across generations and gender as well as race and nationality.

In addition, the recent 2019 Global Human Capital Trends report found 80 percent of this year’s survey respondents now operate almost wholly in teams, with another 23 percent saying that most work is done in teams within a hierarchical framework. Their research this year suggests that shifting toward a team-based organizational model improves performance, often significantly.

Use the following three steps to leverage the brain science of high-performing teams. These insights can be used in any industry and help you consistently build better and more productive teams.

1. Help team leaders set the trajectory with good norming, early on

Research shows that teams go through stages of development on their way to peak performance, and there is a critical juncture that sends them down one of two paths: good norming (respect, safety, trust) or bad norming (competition, apathy, toxic conflict). Team leaders play a critical role in which path the team takes as their initial meetings and actions influence and establish norms. This ultimately determines whether the teams trajectory continues to high performance or spirals into dysfunctions and learned helplessness.

2. Understand the three types of teamwork and how to help teams succeed at each level

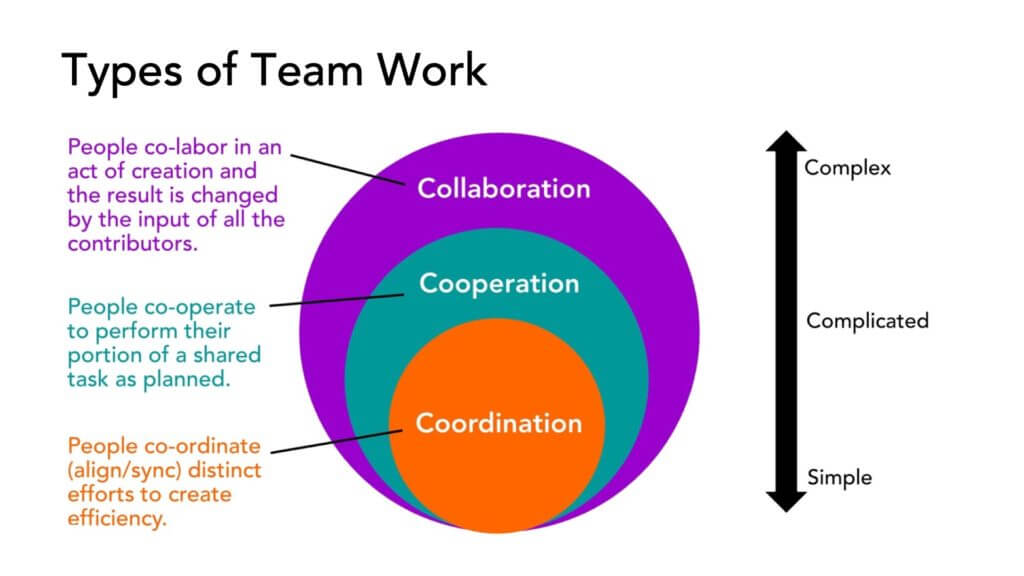

Every day, teams are asked to move between the three types of teamwork: coordination, cooperation, and collaboration. But often, they don’t understand the difference or have the right skills to be successful at each one. Let’s take a look at the definitions and differences:

Coordination is the orchestrated efforts of individuals or groups, to align or synchronize separate actions. They exchange relevant information and resources in support

of each other’s distinct goals. In other words, people coordinate (align/sync) distinct efforts (such as IT upgrading computers and facilities changing out desks) to create more efficiency, but they remain independent.

Cooperation is the coordinated efforts of a group of two or more people to perform their assigned portion of an agreed-upon shared process or task. They are dependent on each other to execute a mutual objective. People co-operate to perform their portion of a shared task, as planned. For example, IT works with Finance and Shipping to ensure that new computers are purchased and delivered on time.

The final type of teamwork, collaboration is a vital necessity for the success of today’s organizations and yet is probably the least understood. I hear the word “collaboration” often in my work with organizations around the world, but people often use the term when they actually mean cooperation or coordination.

Collaboration is the mutual engagement of a group of two or more in a cocreative effort that achieves a shared goal or vision. They are interdependent, with each unique contribution essential to the whole. People colabor in an act of creation, and the result is changed by the input of all the contributors. An example would be several people and departments working together to shift an organization’s culture.

I have found that instead of these being three distinct types of work, collaboration is an umbrella containing cooperation and coordination within it. Some groups and teams may only operate in one or two zones on a daily basis. But more and more, teams are being asked to move across the levels seamlessly. This means that teams often must switch back and forth between goals, intentions, and skill sets, which can be difficult when our work blends together over the course of our daily schedule. We might be in a meeting at 9 a.m. to coordinate with another department, then go right into another meeting where we must cooperate with two other groups, followed by a working project session that is all about collaboration.

The most successful organizations help team members understand the level of teamwork expected of them and provide them with training so they can perform at their best.

3. Teach team leaders how to create psychological safety, belonging, and inclusion

Study after study shows that psychological safety is the critical differentiator of high-performing teams.

The success of the group and the larger organization often depend on people’s ability to speak up, noting potential threats to the group’s or organization’s success. In fact, in Amy Edmondson’s study, the highest performing teams also had the highest reporting rates for errors. This might seem paradoxical but it’s actually a sign of a very healthy team.

When people feel safe enough to mention their errors it means they are also holding themselves accountable, and the whole group benefits from learning from the experience, which supports the team’s success. In addition, when errors are acknowledged, they can be addressed and fixed, rather than ignored to fester into bigger problems later.

Yet, the reality is that many people stay quiet for fear of being embarrassed, rejected, or punished. If you review recent headlines it’s likely you will find stories where someone stayed silent and the consequences were devastating or even fatal. For this reason, psychological safety is especially important—I would argue crucial—for all teams, but especially those operating in high levels of uncertainty and whose members are interdependent.

A new understanding of why exclusion is so uncomfortable for us all.

It is the ground on which belonging and inclusion are built. Did you know that the brain experiences exclusion the same way it experiences physical pain? This finding initially shocked scientists but the results have been replicated numerous times. As Dr. Kipling Williams, a psychologist at Purdue University states, “Being excluded is painful because it threatens fundamental human needs, such as belonging and self-esteem. Again and again research has found that strong, harmful reactions are possible even when ostracized by a stranger for a short amount of time.” For example, a study he conducted with Dr. Naomi Eisenberg at UCLA found that the same parts of the brain activate for social rejection as do for physical pain (the insula and the dorsal anterior cingulate). Using fMRI machines, the researchers created an experience of mild exclusion by having subjects play an online game of catch, called cyberball, with two other players. Then the two players excluded the subject and played without him or her. The pain center of the excluded person lit up, creating a new understanding of why exclusion is so uncomfortable for us all.

When even one person on a team feels excluded or unsafe, the team can no longer reach its full potential or peak performance. Both team members and leaders need to understand how to create and maintain psychological safety and a culture of inclusion.

If you’d like to master the brain science of creating high-performing teams, consider becoming a Facilitator for the Four Gates to Peak Team Performance® program. You can also dive deeper into these concepts in this free guide The Talent Professional’s Guide to Building High-Performing Teams.

Related Blogs

JOIN OUR COMMUNITY

Be the first to know of Dr. Britt Andreatta's latest news and research.